Overview

Though you don’t hear it quite so much anymore, people like to say that we live in a digital age. But what does that mean? And more importantly for this course: what does “digital” mean for writing?

In this chapter, we’ll discuss what we mean when we say “digital” and hopefully push on toward a bit of a definition of “digital authoring.”

The Digital

When we talk about the digital, we are talking about machines, which may surprise you to think about. “Doesn’t,” you might ask, “‘digital’ have something to do with computers?” And of course, you’re right to ask that, because it does. We don’t really use them like this in our day to day lives (ordering food or sending an email or watching cat videos), but the computers we use (and our smartphones are small computers, too) are actually calculating machines, which is to say they are machines designed to perform laborious mathematical operations quickly and efficiently.

So, returning to cat videos and that burrito we just ordered in a little bit, if we understand that our society is digital because it uses digital machines, that might, especially as English majors who are astute and sophisticated readers of texts after all, signal to use that the emergence of “the digital” or of “digital culture” was somehow novel. And we would be right to assume so.

“Digital” refers to a class of machines that are the opposite of analog machines. But, of course, as with any definition by negation, we have simply now introduced a second question: what is (or more properly was) “analog?”

The Analog

Prior to the creation of the first digital computer (which was produced by Alan Turing and a team of mathematicians working on breaking German codes at Bletchley Park during World War II), calculations for things like ballistic missile trajectories were performed using things called analog calculators, which computed the results using things like gears. A simple example of an analog computer is something called a slide rule, which you can learn about here.

But let’s simplify things further. “Analog” shares the same root word with “analogy,” which is a literary device that makes a comparison between two unrelated things. “Shall I compare thee to a Summer’s day,” etc.

Analog machines work the same way: they use a fundamentally unrelated ratio to analogize some other quantity.

Think about a wall clock:

We can read that clock and say “oh, it’s 4 o’clock,” but how do we know that? The small hand, you see, tracks hours while the big hand tracks minutes. Together they inscribe an angle I can read as “4:00.” This is analogy: two hands moving across a circle express a relationship.

Words are also analog. Consider the word “five.” How do we know it represents a quantity? Not to get all philosophical here, but what is “five-ness?” We know that the symbols “five” represent 5 things because we understand the arbitrary, analogical relationship between a sequence of letters and a quantity.

The Analog and the Digital

“But, Dr. Pilsch, what does that tell us about cat gifs?”

We’ll get there.

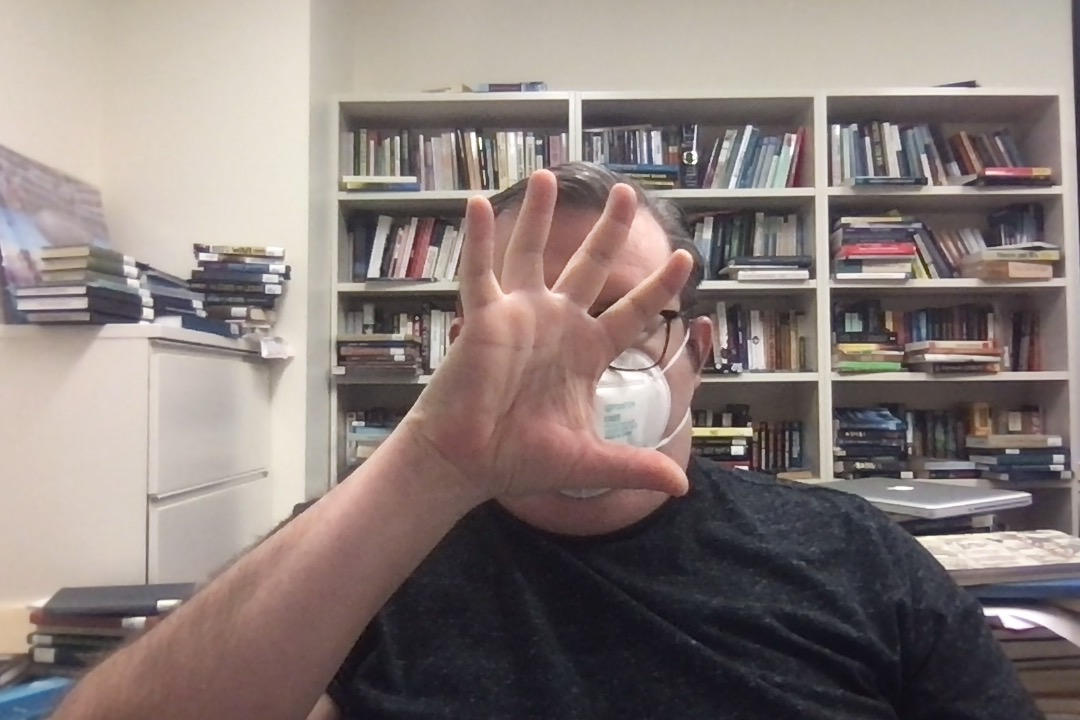

Continuing our digression about the number of, say I hold up five fingers to show you the number five, instead of writing the word “five.”

You can count the number of fingers I am holding up. You could, if you knew some Latin, even say that you counted my five digits to determine the quantity. Another concept is not referenced. There is no mystery relationship. There is only five fingers representing five.

The fancy etymology may be a bit cute, but it’s also the origin of the term “digital,” which originally meant to count on ones fingers.

With the question of the clock, think about a digital clock, in comparison to our analog one earlier:

Like my five fingers, it just displays the digits that represent the quantity of time (4 hours and 0 minutes since midday or midnight). There are no sweeping hands whose angles describe a particular time. There is no analogy.

But Who Cares About the Digital?

As Nicholas Negroponte discusses in Being Digital, shifting from machines that encode information using analogical relationships to ones that store numbers as pure quantity sounds like something that matters to a few scientists but is actually profoundly important for all of our lives.

If you’ve ever seen a vinyl record, you may wonder how it works. Vinyl, an analog technology, actually cuts the shape of the sound waves as they vibrate a medium into the surface of the platter. This is something you can see when you look at the surface of a record under an electron microscope:

There, you can see tiny ridges and valleys that represent the sinusoidal vibrations of the air that would tickle your ears. It’s another analogy: rises and falls in sound waves as rises and falls in the relatively soft surface of a vinyl disc.

But, using math, you can also measure the height of that wave as you record it. Each height can be represented as a number on a computer. If you store enough of these numbers and play them back faster than the human ear can hear, you can produce the illusion of the smooth sinusoidal curve of a vinyl record.

This process, none as sampling, is how CDs and all digital music files work: they are a string of numbers that represent how much sound to play at millisecond-by-millisecond intervals. When this is done, the digital system has approximated the analog representation. It’s a different kind of trick, but most audio research suggests we can’t hear the difference.

This is also why a certain strain of audio geeks will tell you that vinyl sounds “warm.” People claim they can hear the difference between the smooth, analog signal and the blocky, digital one, though there’s no scientific corroboration.

It’s All Numbers

Note that something important has happened in our story, though. When we discussed the digital sound signal, we talked about converting sound into a series of numbers that measure the height of a sine wave through time. We have, I want to emphasize, turned sound into numbers. Numbers that computers are designed to process.

The same is true for anything a computer represents. This webpage? At some level, it’s a bunch of numbers telling the computer what color to display on the two dimensional grid of numbers that represents the screen. Photos are stored the same way: as squares of numbers the each represent a different color (this is why pixelation happens if you zoom far enough toward a digital image).

That report you wrote in your other class? Numbers that the computer translates to particular letters based on a table it has stored elsewhere.

For a computer, literally everything looks like a number.

This relationship, that anything can be quantified, is why “digital” is such an important shift in our culture. You have a student ID number. You have a credit card number. You have a credit score. You have a whole host of other quantities attached to this information: classes, grades, height, weight, hair color, etc. Everything, in a digital society, is a number.

The interesting thing from this, more over, especially from an aesthetic perspective, is that anything can be anything else on your computer. You could play a picture as a song (it might not sound good). A word document could become a picture.

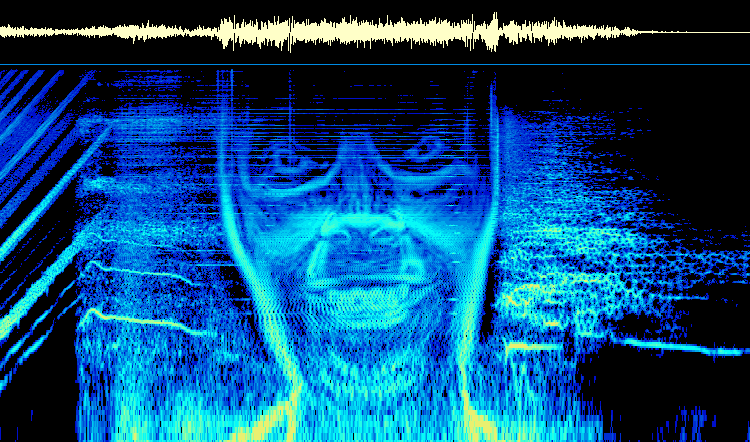

As an example, in the 1999 single “Windowlicker,” Aphex Twin encoded a picture of his face in the sound file so that if you visualize the song with a spectrogram, you get a really disturbing surprise, which you can see below:

On a less avant-garde register, this produces a convergence of media: sound can stand alongside text to enrich the book or the song. With something like a webpage, we can include video, sound, and text all in the same place.

This changes how we think about authoring. When we compose texts for this new age, can or even should we limit ourselves to just one way of encoding information? After all, it’s just numbers.

Next week, we’ll talk more about the theory behind this.