Course Information

Course

- Number: ENGL 353

- Title: History of Rhetoric

- Term: Fall 2021

- Time: MWF 11:30-12:20

- Location: LAAH 301

Instructor

- Name: Andrew Pilsch

- Email: apilsch@tamu.edu

- Office: Zoom

- Office Hours: MF 10:00-11:30

Course Description

The History of Rhetoric is designed to introduce students to the study of rhetoric from the clasiccal period until the end of the 19th century.

Course Learning Outcomes

In this course, students can expect:

- To understand the historical developments of rhetoric as an organized field of study

- To conduct self-directed research on a topic of their choosing

- To write persuasively and masterfully about that topic

Required Texts

You are required to have the following two texts. These are both translations from the Greek. You must have this particular translation for the course (eBooks or PDFs are acceptable):

Both texts are included in Plato: Complete Works, if you have that text from another class.

Assignments

| Assignment Name | Percentage Value | Due Date |

|---|---|---|

| Self-paced Writing Exercises | 20% | Weekly |

| Position Paper #1 | 25% | 10.15.2021 |

| Position Paper #2 | 25% | 11.05.2021 |

| Research Project | 30% | 12.06.2021 |

Assignment Descriptions

Self-paced Writing Exercises (12)

Each week on Wednesday, you will complete a self-paced writing exercise designed to further your understanding of academic writing and prepare you for the task of completing your final research project. These exercises are in support of this courses “Writing Intensive” designation.

The list of writing exercises is at the bottom of this document.

Grading for Writing Exercises

I will be marking your writing exercises as “satisfactory” and “unsatisfactory.” A mark of “unsatisfactory” will be accompanied by comments on how to improve the exercise. If you wish to change an “unsatisfactory” to a “satisfactory,” you may revise your document along the lines of my comments and email me the updated exercise. Assuming the changes are now “satisfactory,” the mark will be changed.

Position Paper (2)

Twice (in weeks 7 and 10), you will produce a short paper (2-3 pages, double-spaced) that takes a position on a particular selection from one of the texts we have read so far in class.

These papers will cover material that has already been discussed in class but has not been covered by a position paper. The first paper, due at the start of week 6, will cover material from the first five weeks of class. The second paper will cover texts from week 6 through week 11.

These position papers ask you to show insights and raise questions in response to the reading and course discussions. Papers that merely summarize an argument or restate the selected passage will receive a failing grade. You need to explain why the passage in question is thought-provoking, or unsettling, or unclear and suggest how you respond to this challenge.

Update

To clarify, this assignment asks you to pick one key point in the text, ideally a single quote or, if not possible, a single very specific claim that is advanced in a few places, and traces why that claim is controversial or challenging. The best papers will also articulate your opinion about the issue or explain why the issue is controversial.

This paper is not intended as a summary of the reading or an overview of the author’s life. I am looking for focused, detailed engagement with specific aspects of the text.

Several successful papers this semester have also related very specific elements of the texts in question to contemporary issues. This is also acceptable, but, again, the idea is to show me you can identify a controversial claim being made in the reading and why that claim is controversial.

Research Project

For a final project, you will be asked to create an artifact that documents the research you have been doing this semester. As a baseline, the artifact should be a 10 page research paper that is well-cited and thoroughly-documented. You can treat the paper as a report-style document, often called a literature review in the business, which is a document reporting on the state of research into a particular topic. This is still a composed essay, so you will need to work out a thesis and draw conclusions.

If, however, you would like to write something more argumentative, you may also complete a thesis-driven essay that argues for a particular point. Is Apuleius more influenced by Aristotle than previously thought? Argue that! Do you see a comparison between St. Augustine and Gorgias no one has noticed before? Argue that! Is there a contemporary text or figure how reminds you of one of the ancient rhetoricians we have studied? Argue that!

Finally, if you would like to explore argumentation outside of academic prose, that is fine. Would you like to write a short story about a medieval initiate monk learning rhetoric for the first time? Cool! Do you want to make a video explaining a Cicero speech that seems relevant to contemporary topics? Do it! If you take the creative route, I would ask you submit a two page paper detailing your thinking in creating the artifact and citing some sources you based your project on.

There is a list of possible topics below, but feel free to propose via email some other topic you would like to explore in your paper.

Possible Topics

- Hellenistic Rhetoric

- Demetrius

- Hermagoras

- Stoicism

- Epicureanism

- Cynicism

- Academicism

- Roman Rhetoric

- Cicero, On Invention

- Cicero, On the Orator

- Cicero, Orator

- Cicero, Speeches

- Cato the Elder

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus

- Seneca the Elder

- Apuleius

- Quintilian

- The Second Sophistic

- Christian Rhetoric

- St. Augustine

- Gregory of Nazianzus

- Classical Tradition and Early Christianity

- Topics

- Rhetorical Education in any of the above periods (BE SPECIFIC)

- Survival and Transmission of Classical Rhetoric

- Philology

- Medieval Rhetorical Practice

- Early Modern Engagements with Rhetorical Theory

- Early Modern Rhetorical Education

- Progymnasmata

Texts to Get Started With

- George A. Kennedy, A New History of Classical Rhetoric

- James Herrick, The History and Theory of Rhetoric

Schedule

Unit 1 – First Unit

Week 1 – First Week

Mon 08/30

- Syllabus

Wed 09/01

Fri 09/03

- Lecture: “What Is Rhetoric?”

Week 2

Mon 09/06

- Lecture: Pericles I

- Read: Pericles, “Funeral Oration”

Wed 09/08

Fri 09/10

- Lecture: Pericles II

Week 3

Mon 09/13

- Lecture: Dissoi Logoi I

- Read: Anonymous, Dissoi Logoi

Wed 09/15

Fri 09/17

- Lecture: Dissoi Logoi II

Week 4

Mon 09/20

- Lecture: Gorgias I

- Read: Gorgias, “Encomium for Helen”

Wed 09/22

Fri 09/24

- Lecture: Gorgias II

Week 5

Mon 09/27

- Lecture: Plato, Gorgias I

- Read: 447a-468b

Wed 09/29

Fri 10/01

- Lecture: Plato, Gorgias II

- Read: 468b-486d

Week 6

Mon 10/04

- Lecture: Plato, Gorgias III

- Read: 486d-506b

Wed 10/06

Fri 10/08

- Lecture: Plato, Gorgias IV

- Read: 506b-End

Week 7

Mon 10/11

- Lecture: Isocrates

- Read: “Against the Sophists”

Wed 10/13

Fri 10/15

- Lecture: Alcidamas

- Read: Alcidamas, “Against the Sophists”

- Position Paper #1 Due

Week 8

Mon 10/18

- Lecture: Plato, Phaedrus I

- Read: 227a-244a

Wed 10/20

Fri 10/22

- Lecture: Plato, Phaedrus II

- Read: 244a-257c

Week 9

Mon 10/25

- Lecture: Plato, Phaedrus III

- Read: 257c-274b

Wed 10/27

Fri 10/29

- Lecture: Plato, Phaedrus IV

- Read: 274b-End

Week 10

Mon 11/01

- Lecture: Aristotle I

- Read: Aristotle, Book I: All Chapters

Wed 11/03

Fri 11/05

- Lecture: Aristotle II

- Read: Aristotle, Book II: Chapters 1-3, 12-13, 18-25

- Position Paper #2 Due

Week 11

Mon 11/08

- Lecture: Aristotle III

- Read: Aristotle, Book III: Chapters 1-2, 13

Wed 11/10

Fri 11/12

- Lecture: Aristotle IV

Week 12

Mon 11/15

- Lecture: Rhetorica ad Herennium I

- Read: Rhetorica ad Herennium, Book 1

Wed 11/17

Fri 11/19

- Lecture: Rhetorica ad Herennium II

Week 13

Mon 11/22

- Final Project Introduction

Wed 11/24

No Class

Reading Day

Fri 11/26

No Class

Thanksgiving

Week 14

Mon 11/29

- Work On Your Projects

Wed 12/01

- Work On Your Projects

Fri 12/03

- Work On Your Projects

Week 15

Mon 12/06

- Final Project Due at 11:59PM

Course Policies

Email Hours

I am available to answer email from 9:00am until 5:00pm Monday through Friday. Emails arriving outside of that time will be answered at my earliest convenience, but do not count on a quick answer to emails sent late at night or on the weekends.

Office Hours

All office hours are virtual. Do not, under any circumstances, come to my office.

University Policies

COVID-19 Statement

To help protect Aggieland and stop the spread of COVID-19, Texas A&M University urges students to be vaccinated and to wear masks in classrooms and all other academic facilities on campus, including labs. Doing so exemplifies the Aggie Core Values of respect, leadership, integrity, and selfless service by putting community concerns above individual preferences. COVID-19 vaccines and masking — regardless of vaccination status — have been shown to be safe and effective at reducing spread to others, infection, hospitalization, and death.

Attendance Policy

The university views class attendance and participation as an individual student responsibility. Students are expected to attend class and to complete all assignments.

Please refer to Student Rule 7 in its entirety for information about excused absences, including definitions, and related documentation and timelines.

Makeup Work Policy

Students will be excused from attending class on the day of a graded activity or when attendance contributes to a student’s grade, for the reasons stated in Student Rule 7, or other reason deemed appropriate by the instructor.

Please refer to Student Rule 7 in its entirety for information about makeup work, including definitions, and related documentation and timelines.

Absences related to Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 may necessitate a period of more than 30 days for make-up work, and the timeframe for make-up work should be agreed upon by the student and instructor” (Student Rule 7, Section 7.4.1).

“The instructor is under no obligation to provide an opportunity for the student to make up work missed because of an unexcused absence” (Student Rule 7, Section 7.4.2).

Students who request an excused absence are expected to uphold the Aggie Honor Code and Student Conduct Code. (See Student Rule 24.)

Course Policy on Makeup Work

Under Student Rule 7.4, I am under “under no obligation to provide an opportunity for the student to make up work missed because of an unexcused absence.” As such, no late work will be accepted this semester.

Academic Integrity Statement and Policy

“An Aggie does not lie, cheat or steal, or tolerate those who do.”

“Texas A&M University students are responsible for authenticating all work submitted to an instructor. If asked, students must be able to produce proof that the item submitted is indeed the work of that student. Students must keep appropriate records at all times. The inability to authenticate one’s work, should the instructor request it, may be sufficient grounds to initiate an academic misconduct case” (Section 20.1.2.3, Student Rule 20).

You can learn more about the Aggie Honor System Office Rules and Procedures, academic integrity, and your rights and responsibilities at aggiehonor.tamu.edu.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Policy

Texas A&M University is committed to providing equitable access to learning opportunities for all students. If you experience barriers to your education due to a disability or think you may have a disability, please contact Disability Resources in the Student Services Building or at (979) 845-1637 or visit disability.tamu.edu. Disabilities may include, but are not limited to attentional, learning, mental health, sensory, physical, or chronic health conditions. All students are encouraged to discuss their disability related needs with Disability Resources and their instructors as soon as possible.

Title IX and Statement on Limits to Confidentiality

Texas A&M University is committed to fostering a learning environment that is safe and productive for all. University policies and federal and state laws prohibit gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, including sexual assault, sexual exploitation, domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking.

With the exception of some medical and mental health providers, all university employees (including full and part-time faculty, staff, paid graduate assistants, student workers, etc.) are Mandatory Reporters and must report to the Title IX Office if the employee experiences, observes, or becomes aware of an incident that meets the following conditions (see University Rule 08.01.01.M1):

- The incident is reasonably believed to be discrimination or harassment.

- The incident is alleged to have been committed by or against a person who, at the time of the incident, was (1) a student enrolled at the University or (2) an employee of the University.

Mandatory Reporters must file a report regardless of how the information comes to their attention – including but not limited to face-to-face conversations, a written class assignment or paper, class discussion, email, text, or social media post. Although Mandatory Reporters must file a report, in most instances, you will be able to control how the report is handled, including whether or not to pursue a formal investigation. The University’s goal is to make sure you are aware of the range of options available to you and to ensure access to the resources you need.

Students wishing to discuss concerns in a confidential setting are encouraged to make an appointment with Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS).

Students can learn more about filing a report, accessing supportive resources, and navigating the Title IX investigation and resolution process on the University’s Title IX webpage.

Statement on Mental Health and Wellness

Texas A&M University recognizes that mental health and wellness are critical factors that influence a student’s academic success and overall wellbeing. Students are encouraged to engage in proper self-care by utilizing the resources and services available from Counseling & Psychological Services (CAPS). Students who need someone to talk to can call the TAMU Helpline (979-845-2700) from 4:00 p.m. to 8:00 a.m. weekdays and 24 hours on weekends. 24-hour emergency help is also available through the National Suicide Prevention Hotline (800-273-8255) or at suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Department Policies

University Writing Center

The mission of the University Writing Center (UWC) is to help you develop and refine the communication skills vital to success in college and beyond. You can choose to work with a trained UWC peer consultant in person or via web conference or email. Consultants can help with everything from lab reports to application essays and at any stage of your process, from brainstorming to reviewing the final draft. You can also get help with public speaking, presentations, and group projects. The UWC’s main location is on the second floor of Evans Library; there’s also a walk-in location on the second floor of the Business Library & Collaboration Commons. To schedule an appointment or view our helpful handouts and videos, visit writingcenter.tamu.edu. Or call 979-458-1455.

Diversity Statement

It is my intent that students from all diverse backgrounds and perspectives be well-served by this course, that students’ learning needs be addressed both in and out of class, and that the diversity that students bring to this class be viewed as a resource, strength, and benefit. It is my intent to present materials and activities that are respectful of diversity: gender, sexual orientation, disability, age, religion, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, race, culture, perspective, and other background characteristics. I encourage your suggestions about how to improve the value of diversity in this course.

Writing Exercises

Exercise 1 - Introductions

Introduce yourself! For this first writing exercise, please provide the following information:

- Your name

- Your pronouns

- Your major and year

- Your favorite book and briefly why

- Your interest in rhetoric or why you took the course

- Your previous experiences with rhetoric, either at Texas A&M or elsewhere

When you have answered these questions, submit your document on the dropbox on Canvas.

Exercise 2 - Definitions of Rhetoric

We talked last week about the origins of the term “rhetoric.” This course will concern itself with the mostly messy, often contradictory history of this term. One consequence of this history is that definitions of the term “rhetoric” proliferate. Here are a couple of my favorite:

- “For he is the best orator who by speaking both teaches, and delights, and moves the minds of his hearers.” (Cicero)

- The Orator is “a good man speaking well.” (Quintilian)

- “The duty and office of Rhetoric is to apply Reason to Imagination for the better moving of the will.” (Francis Bacon)

- “Rhetoric is the art which seeks to capture in opportune moments that which is appropriate and attempts to suggest that which is possible.” (John Poulakos)

For today’s exercise:

- Having read the above definitions, pick the one you find most compelling (“compelling” here can be good or bad).

- Write a few paragraphs explaining in detail what it is about this definition that compels you. Be specific

- Use Google to find out a bit about the speaker (making sure you get the correct Francis Bacon; there are two famous people with that name!)

- Note some sources you used in a paragraph, commenting on what was good or bad about the source (you don’t have to use proper citations at this point).

- Write a paragraph or two explaining if the time period or biographical information clarifies your understanding of the definition. If so, how? If not, why not?

You should have around one to two pages of double-spaced writing at this point. If not, make sure you have explained your position and your research with enough thoroughness. Then submit to the Dropbox on Canvas.

Exercise 3

Read “The Cost of Achieving Community: Pericles’ Funeral Oration” by Jim Mackin, which concerns itself with some of the rhetorical aspects of Pericles’ speech. What, to your reading, is the most controversial claim made in the text?

Quote the claim in the text (again, not worrying yet about citing it properly). Use a block quote if the selection is longer than four lines, otherwise quote your selection using quotation marks.

After the quote, explain why you chose it as controversial? Do you agree with the claim? Do you disagree? What criteria helped you decide what was controversial? Did the author signal that this claim was controversial or are you basing your selection off of your personal interests?

Write up your answer to these questions in a 1-2 page set of notes (don’t worry about it being a formal essay) and submit to the dropbox on Canvas.

Exercise 4

Read “Discovering a Topic, Preparing for Discussion.”

Think about three topics you could use for the first position paper and analyze them given the rubric described in the above chapter. Which do you think is most effective? Why?

Write up your answer, including the three possible topics, as a 1-2 page collection of notes and submit to the dropbox on Canvas.

Exercise 5

Read “Ordering Evidence, Building an Argument”

Given the three topics you outlined in last week’s assignments, what kind of evidence would you need to argue for the controversial nature of each? Using the methods described in this chapter, create three rough outlines of the position paper you would write based on each claim.

Now, which one seems like the most compelling? Which will make the strongest first paper? Why?

Along with the three outlines, include some thoughts on the above list of questions and submit the whole thing to the dropbox on Canvas.

This will be the final writing exercise in preparation for the first position paper. Writing Exercise 7 will be peer review for this paper.

Exercise 6

With this exercise, we will be shifting to the research paper, to be completed at the end of the semester.

One of the first tasks of a scholar is positioning their work within the conversation. And to do that, a scholar must have some understand of the state of the field. There are many ways to do this, but a quick one is to use various reference works designed to help situate new researchers within a topic.

For this exercise, I have provided on Canvas a chapter from The Present State of Scholarship in the History of Rhetoric (3rd Edition; 2010) that summarizes work done on the classical period (Greek and Roman rhetoric, which is the topic of the research project). Read over this document, which includes an extensive bibliography, and write up some notes on two topics:

- What was it like reading this kind of document? Have you read something like this before? Did you find it helpful? Or confusing? What jargon did the document use?

- What topics interested you? What would you like to know more about? Why?

Submit your notes on these two topics to the dropbox on Canvas.

Exercise 7

Conducting peer review is an important part of the writing process, even though it often feels like a chore. The reason being that, as we write, we often do not see the parts of our paper that don’t make sense or have grammatical errors and so forth because we are so familiar with what we are trying to say that it blocks us from seeing what we did say. Thus, getting someone else to look over our paper can greatly help clarify and improve our argumentation.

For this week’s exercise, arrange with two classmates to exchange drafts (you can do this virtually or in person) and read each others’ documents over. There is a peer review checklist posted to Canvas. You will complete this document for each of your two peers, provide copies to your two peers, and turn in the checklists you completed to the dropbox on Canvas for credit on this lab.

Exercise 8

You have been provided a list of topics for the research paper. How are you going to choose which to write about? Becoming familiar with unfamiliar topics is key to starting the research process. Perhaps something I’ve said in class sparked your interest? Perhaps you encountered something reading from The Present State of Scholarship in the History of Rhetoric about which you’d like to know more?

In any case, for this writing exercise, spend some time researching the list of provided topics. Wikipedia is an excellent source for starting research, as is The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

If you have another topic in mind, spend some time with the list nonetheless, but also do some more background work on your proposed topic.

Write up, in the form of notes, an account of your research. What sources did you consult? What else do you want to know?

Conclude by picking a topic (I won’t hold you to it at this point) and discussing why you chose what you chose.

Exercise 9

Now that you have a topic in mind, it’s time to start doing some research. Finding sources can be baffling at first, especially for a paper such as our research assignment.

There are a few things to remember and some tools that can help:

Kinds of Sources

When we talk about citing sources in a research paper, we mean two things: primary sources and secondary sources. Primary sources refer to texts from the period in question. So, for instance, in our course, Plato’s Phaedrus would be a primary source, as it was from ancient Greece and about rhetoric. Jacques Derrida’s “Plato’s Pharmacy” is a secondary source, as it is a work of criticism about a primary source.

We also have to evaluate the scholarly nature of our secondary sources. As a rule, we want scholarly sources that have been peer-reviewed, so books published by university presses (they mostly have “university” in the name of the publisher, though Routledge, Bloomsbury Academic, and Palgrave Macmillan are considered scholarly as well) or journals that have peer-reviewed their articles. Articles published in national news magazines (such as Time or The Atlantic) can usually be used as a secondary source. The big questions to ask when evaluating the scholarly nature of a secondary source include “who published this?,” “who wrote this (and what is their job)?,” “does this seem like an authoritative publication?,” “is the article advocating a particularly biased opinion or using a neutral tone to convey knowledge?” (the latter is preferable).

We treat our sources differently depending on their character. Primary sources are examples: they show cultural or philosophical or other attitudes at a time and a place. For instance, I could cite a science fiction novel about alien invasion as an example of Cold War paranoia but I could not cite it as an example that pod people walk among us. Secondary sources are treated as authoritative voices in our text, they support our arguments by adding the ethos of their authors, they provide a starting point (by providing our argument an entry point into the conversation), or they provide us negative examples to bounce off of (by showing how existent scholarship is wrong or incomplete).

A Note on Wikipedia

Wikipedia is often, but not always, a well-researched compendium of human knowledge. As a rule, using it as a starting place, especially in topics like the history of rhetoric and philosophy which tend to be pretty robust on the site, is advisable, but verify with a scholarly source anything you find on Wikipedia. Don’t cite Wikipedia as an authority.

Finding Sources

The best way to find scholarly sources for your research is Google Scholar. It is a search engine for scholarly sources and indexes most academic journals and scholarly books. Use it as you would Google, though the indexing on Google Scholar does tend toward STEM fields, so sometimes you have to be creative in your terms. As this research paper draws from fairly specific classical terminology, you shouldn’t have that problem, but you will most likely want to include “rhetoric” in your search terms, so that you have some scope of the problem.

You may also want to think about related searches as you conduct research. Are their particular people associated with your topic who you could also search for? Are their concepts related to your topic that you could also search for? Can you find general information about the period in a more broadly scoped textbook to include? Get creative with the searches you are conducting!

Sources indexed by Google Scholar may not necessarily be open access, so the task falls to you to acquire the pieces you have found. Thankfully, Texas A&M Libraries makes this fairly easy.

Getting Sources

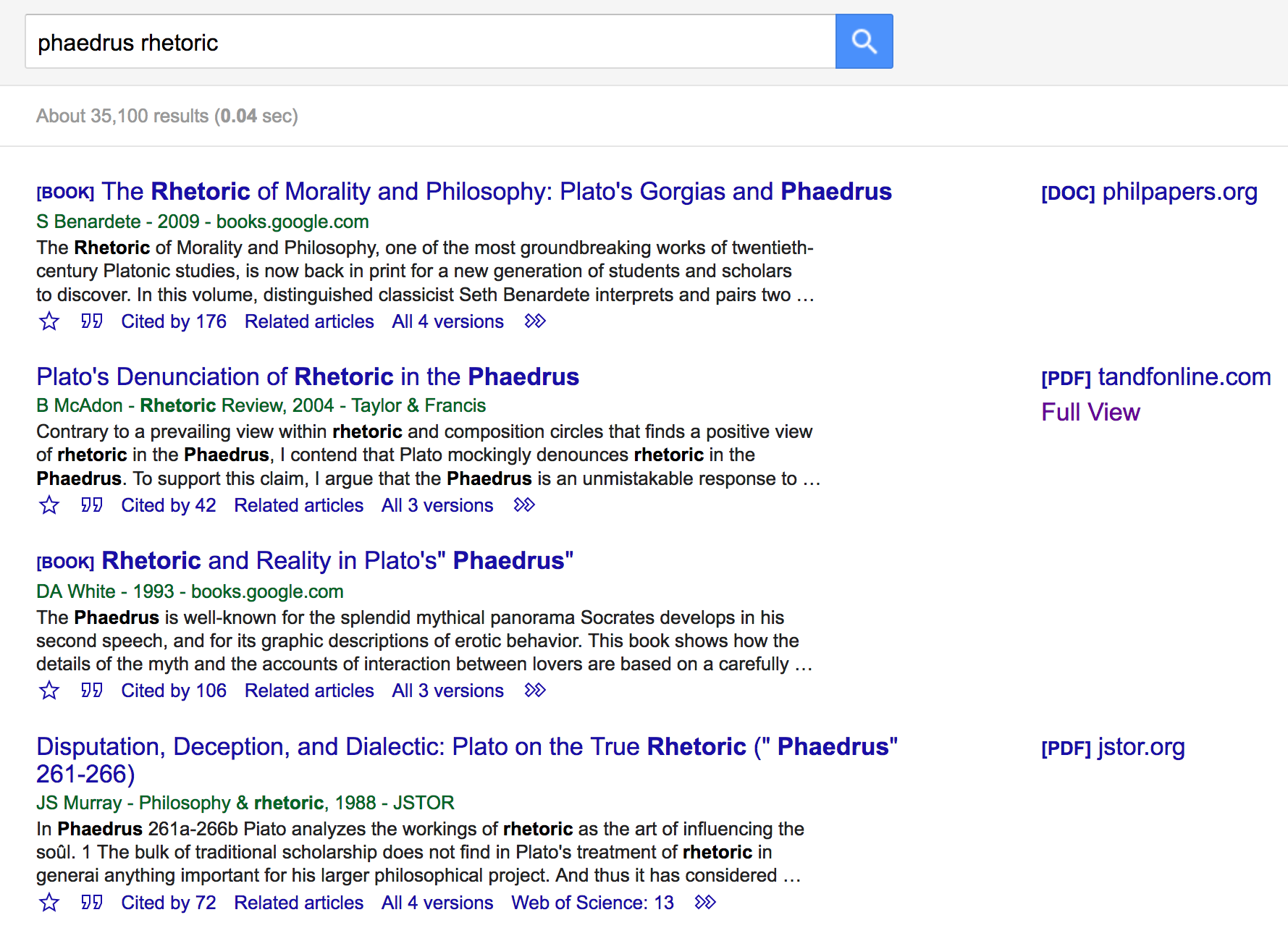

As an example, I’m going to search for phaedrus rhetoric in Google Scholar. It produces several results, which you can see below:

The four results are:

- The Rhetoric of Morality and Philosophy: Plato’s Gorgias and Phaedrus by S. Bernadete

- “Plato’s Denunciation of Rhetoric in the Phaedrus” by B. McAdon

- Rhetoric and Reality in Plato’s “Phaedrus” by D.A. White

- “Disputation, Deception, and Dialectic: Plato on the True Rhetoric (‘Phaedrus’ 261-266)” by J.S. Murray

Results 1 and 3 are tagged [BOOK] by the results, so we can assume they are printed books. Results 2 and 4 are not tagged at all, so we know they are journal articles. Below the titles, the publication information is listed. Result 2 was published in Rhetoric Review in 2004 and Result 4 was published in Philosophy & Rhetoric in 1988.

So, how to get those?

We are in luck, as Result 2 (the McAdon article) has “Full View” as a link option to the right of the main result column. That means Google Scholar has found a copy of the article on the web. We can click it and read about denunciation (though, being a journal article, the piece will likely have an abstract, which we should read first to determine its relevance to our research).

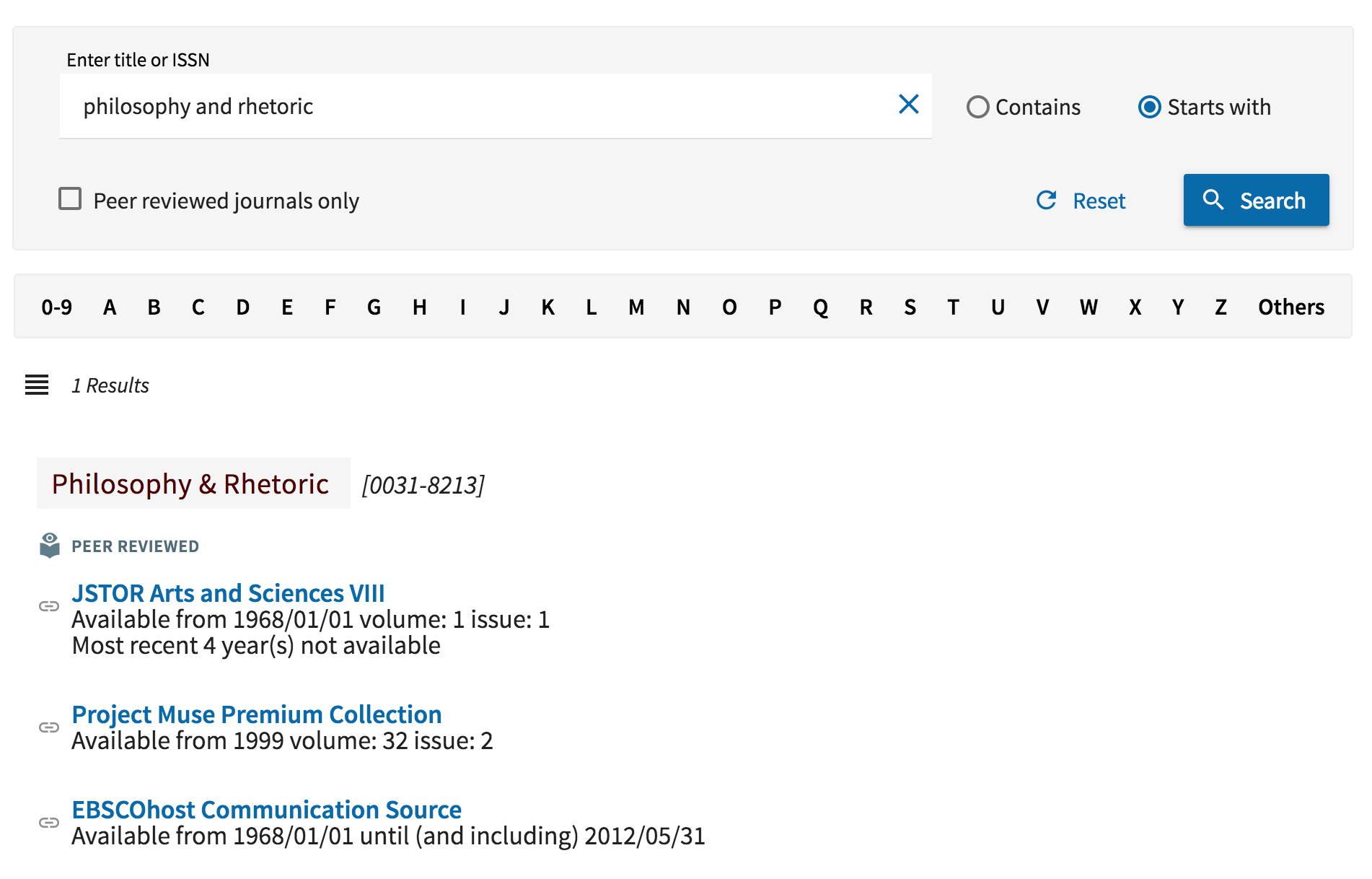

However, Result 4 (the Murray article) does not have a “Full View” option. To access it, we must turn to the library’s page, specifically the list of electronic journal. We can search for “Philosophy and Rhetoric,” which produces the following results:

The first result reads:

JSTOR Arts and Sciences VIII open_in_new

Available from 1968/01/01 volume: 1 issue: 1

Most recent 4 year(s) not available

And the second reads:

Project Muse Premium Collection open_in_new

Available from 1999 volume: 32 issue: 2

Both results list the restrictions on that particular collection. JSTOR does not have recent articles, which does not matter to us because our article was published in 1988. Project MUSE has recent articles but does not have anything before 1999. So, it looks like we should click on the JSTOR result.

On the JSTOR page for Philosophy & Rhetoric, we find the list of all issues, expanding on “1980s” and finding four issues for 1988. If we click on all of them, we eventually find the Murray article in Vol. 21, No. 4. We can download the PDF of the article or read it online, as we prefer (though the PDFs let you highlight and copy text, so they can be useful for transcribing quotes).

Note: If you cannot find access to a journal through the A&M library, you can use ILL (discussed below to get a copy of the journal article from another library).

Finding a Book

Now that we found a journal article in one of Texas A&M’s library databases, how to find the book? We have two options:

- Go to the library

- Use ILL to access the book

Finding Books in the Library

To find out if A&M owns the book in question and if the book is not checked out, search in the catalog using the search box provided on the front page.

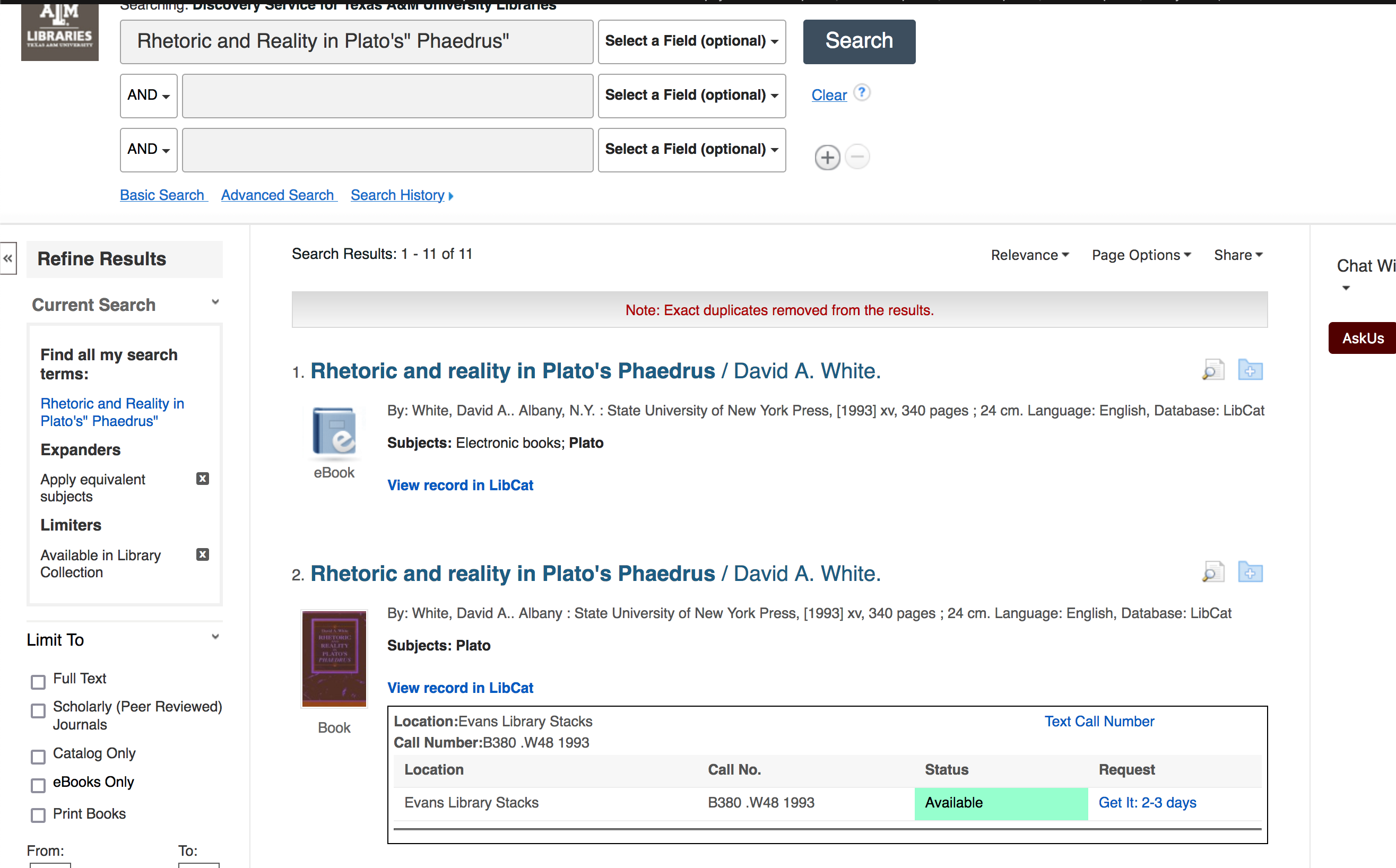

If I search for our third search result from Google Scholar (Rhetoric and Reality in Plato’s “Phaedrus” by D.A. White), I get the following:

I get two results. The first is listed as an eBook and the second is a book.

So it looks like, if I want, I can avoid going outside today and just get the eBook. But, say I really want to smell old paper and feel the rough pages of the book as I read. The second result indicates the book is available (Green status with “Available”) and that the call number is B380 .W48 1993 in Evans Library.

When I get to Evans, I would consult the guide by the elevators to know which floor I need to go to (I believe B is on Floor Six) and head out for my book.

You may check out books at the circulation desk on the ground floor of Evans library or at any of the self-checkout kiosks throughout the library. If you decide you don’t want a book, find the re-shelving areas around the library and a library worker will re-shelve the book for you. Never re-shelve a book yourself, that’s how books get lost.

There are also scanners and photocopiers available around Evans, if you would like to make a digital or paper copy of part of the book.

Accessing ILL

We used the third result, because the first result from Google Scholar (The Rhetoric of Morality and Philosophy: Plato’s Gorgias and Phaedrus by S. Bernadete) produces the following results:

The first two results are listed as “Academic Journal Articles.” These are book reviews, which are other scholars discussing the merits of a work. Results like this mean A&M does not own the book in question.

To access it, we would need to use the Interlibrary Loan (or ILL) service. A&M can get most anything through ILL, if you are willing to wait for it. To access ILL, click here and log in. Once you are connected, in the left sidebar, you will see a number of options under “New Requests.”

ILL has many options for getting text. If you would like another library to send you a print book, click on “Book.” If you have access to the table of contents and know which section you would like (say one chapter or one article in an edited collection), click on “Book Chapter.” If you need a journal article, click on “Article.”

You will be taken to a form that will ask you some minimal information about the book. When you have completed it, the ILL office (who are amazing) will get on finding your text.

A couple of things to note:

- ILL is totally free for you to use

- You can access anything via ILL, not just stuff at other libraries

- They can pull books from the stacks and store them for you at the front circulation desk

- They can also scan chapters from books owned by A&M

- Electronic copies of articles or book chapters are always much faster than getting the physical book

- I have received requested chapters within 4 hours when the book is in A&M’s collection

Your Task

Now that you know a bit about finding resources at A&M, begin to do some research for your paper. Identify four potential sources you would use based on the topic you have already selected. Write up how you can access them (if you need to go to the library or use ILL, you may want to start the process), so that you have them on-hand, as we will be working with these sources in Exercises 11 & 12.

Submit a 1-2 page document covering your sources, how you found them, and a paragraph or two about additional research you need to conduct for the research paper.

Exercise 10

We will be conducting peer review for the second position paper this week. Once again, work with two other classmates to evaluate and improve one another’s work.

You will have the same peer review checklist as in Writing Exercise 7 on Canvas.

In addition to the two reports, you will also submit a document—one or two short paragraphs—, detailing what strategies you adopted this time, if any, to improve your peer review experience, either in soliciting feedback or giving better feedback. What else would you like to try?

Submit this reflection along with the two checklists you completed for your peers to the dropbox on Canvas.

Exercise 11

Now that we have identified a number of sources, we need to focus on summarizing our sources. Summarizing is the process of condensing an argument into a focused set of sentences. These sentences need to be our own words, but can use light quoting, especially for key concepts introduced by the author of the text. Summarization serves a number of purposes, but the main one is reminding us of our own reading, answering “what was this article about, again?” Additionally, we can use these summaries we write in our own writing.

Writing Summaries

A summary needs to have two parts: an overview of the entire argument and an account of that argument’s use for our current research project. So, for instance, imagine you were reading an encyclopedia entry by a Dr. Joseph Palpatine on the topic of ancient rhetoric. The article has some particularly good stuff on the second sophistic, which is the topic of your research paper. You might write the following summary:

Palpatine offers a rich and detailed account of rhetoric in ancient Greece and Rome, paying special attention to Rome and both the republic and imperial periods. Palpatine places particular interest on rhetorical education and the ways in which young orators attained their training.

The entry offers a particularly good discussion of this period and it’s educational methods. Palpatine has a particularly striking defense of Philostratus, which will help in the section on the veracity of Lives of the Sophists. He suggests that while the lives may be based on heresay, they are our only source for information on the period and ignoring the accounts offered there will do more damage.

The first paragraph in my summary gives an overview of the article. The second focuses on what I’m interested in it for (the defense of Lives of the Sophists).

We write summaries in the way I described above because we need two things from them: to introduce a general summary of the work and to highlight what we are specifically interested in.

When I went to talk about Lives of the Sophists, I might add the following: “Palpatine, in an encyclopedia article on ancient rhetoric, defends Philostratus on the grounds that Lives of the Sophists is often our only source for information from the period.” So, I used my introductory paragraph to remind my readers what the overall argument of the piece was and to provide my particular interest in it.

If I had a source I wanted to discuss at more length, say some of the entries in Lives of the Sophists itself, I might need a longer summary, but I would still want to rely on my overall summary to frame the text when I first talk about it. This helps establish ethos by explaining to our readers what the text is and why they can trust what it says.

Your Task

Taking the sources you find in the previous exercise, write short summaries for each. Try to give an account of what the article is about, including its most important claims. Remember that the summary needs to brief (4-5 sentences at most). Try to also include a second paragraph explaining your own interest in each source.

Submit these summaries to Canvas.

Exercise 12

The final step to incorporating research material is citation. Citation practices are often discussed as a means of preventing plagiarism, which they are, of course, but, more importantly, citations allow later scholars to trace source material, verify our claims, and to extend the scholarly conversation we are participating in.

Purdue University’s OWL is one of the best resources on academic research writing. Review the following pages on the OWL covering MLA 9 citations:

- In-text Citation

- Formatting Quotations

- Pay special attention to the differences between block and inline quotes

- Endnotes and Footnotes

- Footnotes are often useful to quickly summarize a lot of research, especially when it isn’t directly relevant to your writing

- Works Cited Pages: Basics

After you have finished that reading, produce a works cited page for the sources you have been working with in the last few exercises. Submit this to Canvas.